The Disaster of Groupthink And What To Do Differently

What does a dramatic plunge in Marks & Spencer’s share price have in common with America’s shambolic attempt to invade Cuba? What unites the collapse of one of the world’s most prestigious airlines with the failure to predict one of the most infamous attacks in military history? The answer is groupthink. All of the above, from M&S’s late-’90s lurch to the farrago of the Bay of Pigs, from Swissair’s unforeseen demise to the horror of Pearl Harbour, is widely cited as classic examples of what happens when people reach a consensus without giving due thought to the alternatives.

The term “groupthink” was initially coined in 1952 by William H Whyte, a writer for Fortune magazine. Whyte described the phenomenon as “an open, articulate philosophy. A philosophy which holds that group values are not only expedient but right and good as well”.

Research into the theory began in earnest almost two decades later when Irving Janis, a psychologist at Yale University, investigated the effect of extreme stress on group cohesiveness. According to Janis, groupthink should have an “invidious connotation”.This is because it arises from “a deterioration in mental efficiency, reality testing and moral judgments”.

The mindset of groupthink seemingly explains unthinking conformity. It’s clear that disastrous decisions can result. Groupthink leads to disastrous decisions in a number of settings, from the boardroom to cults. A lack of independent thought and collective views also seem to result from social media, including Twitter and Facebook.

A worry for many organisations is that the evidence supporting a general propensity towards groupthink can appear overwhelming. Managers can often find the phenomena to be difficult to avoid, or even to solve. Encouragingly, however, new research suggests otherwise.

Psychology explains groupthink as confirmation bias. We exhibit bias when we attach more significance to information that confirms a hypothesis we already favour and less to information that contradicts it.

Greek historian Thucydides referred to it in his account of the Peloponnesian War when he wrote of people’s “habit to entrust to careless hope what they long for and to use sovereign reason to thrust aside what they do not fancy”. In the Novum Organum, his 1620 treatise on inductive reasoning, philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon summed up the problem as follows: “The human understanding when it has once adopted an opinion… draws all things else to support and agree with it.”

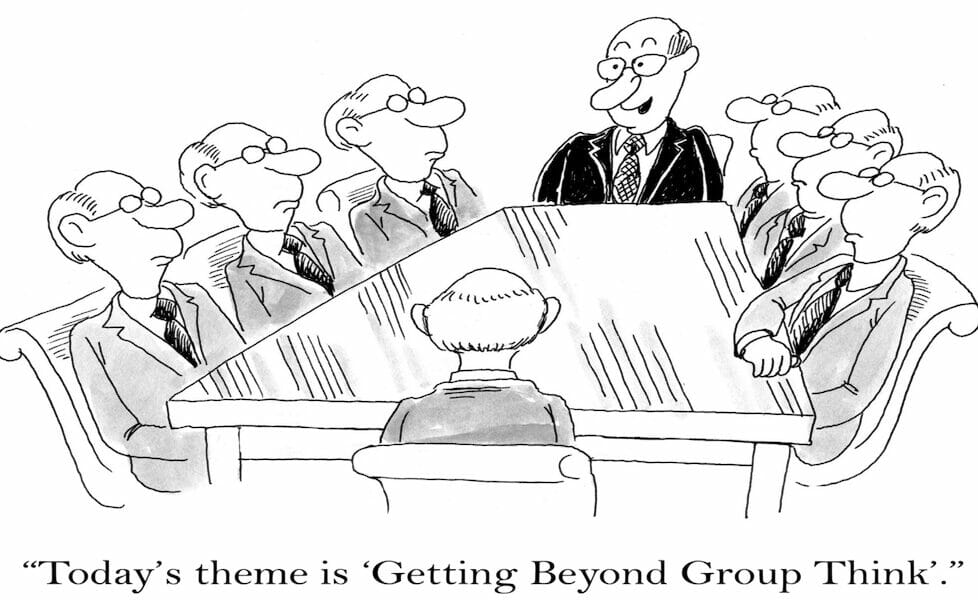

Almost anyone who has sat through a business meeting will have experienced something that chimes with these remarks. When a group assembles to solve a problem, the goal should be a decision of improved quality. Solving the problem needs a variety of perspectives, which is not the case in this situation. The rush to judgment can be both rapid and reckless with hindsight.

A better understanding of how we obtain evidence that influences our subsequent weighting could help guard against this unfortunate propensity. Might it be possible to reduce the threat of groupthink by structuring the decision-making process differently?

Findings from a study undertaken by economists from LSE and the University of Nottingham showed reverse confirmation bias when people share and consider evidence. The subjects placed much more weight on conflicting proof because they were made to realise how little they knew. The “illusions of invulnerability” often melted away in the heat of authentic debate and dialogue.

It is important to stress that these are remarkably subtle effects. They underline the age-old axiom that we frequently succeed only in raising further questions in striving to find answers. Precisely how we should interpret such conclusions will undoubtedly require further research. However, the implications are perhaps altogether more straightforward for businesses and their managers.

Janis posited that a critical method of defending against groupthink should be to cast at least one group member in the role of devil’s advocate. The benefits of this strategy were further highlighted only recently in a Stanford Graduate School of Business study that recommended every team feature a contrarian who is “constructive and careful in communication” and engenders “healthy conflict”.

Our research seems to – dare we say it? – confirm as much. Groupthink thrives in the absence of genuine deliberation. Ultimately, the lesson is that it is good to talk at its simplest.

Dr Jeroen Nieboer is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in the London School of Economics’ Department of Social Policy. His areas of research include behavioural economics, cooperation, decision-making under risk and group decision-making.